Net book value shows what an asset is worth after accounting for depreciation.

Most people assume an asset’s value is whatever they paid for it. But over time, wear and tear take their toll, and its real worth changes. That’s where NBV comes in—it tells you what’s left of an asset’s value on the books after depreciation.

Think of it like this: You buy a company vehicle for $30,000. A few years later, after accounting for depreciation, its NBV might be $15,000. That’s the number that matters when assessing assets for financial reporting or resale.

So, how does NBV impact your financial decisions?

Benefits of Net Book Value

Understanding the benefits of Net Book Value helps businesses manage their assets effectively and make informed financial decisions. From performance evaluation to tax advantages, NBV plays an important role in maintaining accurate records and ensuring long-term financial stability.

Performance Evaluation

NBV helps businesses measure how effectively an asset contributes to revenue generation. By regularly calculating NBV, companies can track changes in asset value and determine if an asset is being used efficiently.

If the NBV of an asset declines faster than expected, it may indicate inefficiencies, prompting businesses to reassess their usage strategies or consider replacements.

Regulatory Compliance

Accounting standards, such as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), require businesses to report asset values correctly.

Calculating NBV ensures compliance with these standards, reducing the risk of financial misstatements and potential regulatory penalties. Proper NBV calculations also help maintain transparency in financial reporting, which is crucial for investors, auditors, and stakeholders.

Tax Benefits

Depreciation is a key factor in tax calculations, and NBV helps businesses determine the correct deductions. By accurately tracking asset depreciation, companies can reduce taxable income, lowering their overall tax burden. This makes NBV an essential component of financial planning and tax strategy.

Depreciation Tracking and Financial Management

NBV provides insights into the remaining useful life of an asset. Businesses can use this information to plan for future expenses related to maintenance, repairs, or replacements. Knowing an asset’s NBV helps companies allocate budgets effectively and avoid unexpected costs, ensuring smooth operations.

Net Book Value Formula

Net Book Value is calculated by subtracting accumulated depreciation from the original cost of an asset. The original cost, also known as historical value, is the purchase price of the asset.

NBV Formula:

Net Book Value = Original Asset Value – Accumulated Depreciation

To calculate NBV, follow these steps:

Step 1. Identify the Original Purchase Price of the Asset

The original purchase price, also known as the historical cost, is the amount paid to acquire the asset. This includes the purchase price itself and any additional costs necessary to bring the asset into use, such as transportation, installation, or setup fees.

Step 2. Determine the Accumulated Depreciation

Depreciation represents the reduction in an asset’s value over time due to usage, wear and tear, or obsolescence. The accumulated depreciation is the total depreciation recorded from the time the asset was acquired up to the current date.

The method used to calculate depreciation—such as straight-line, declining balance, or units of production—affects how the depreciation amount is determined.

Step 3. Subtract the Accumulated Depreciation from the Original Asset Value

Once the original purchase price and accumulated depreciation are known, apply the Net Book Value formula:

Step 4. Net Book Value = Original Asset Value – Accumulated Depreciation

This final step provides the current value of the asset on the company’s financial statements, reflecting its worth after depreciation has been accounted for.

Example Calculation

ABC Company purchased an asset for $12,000 on January 1, 2024. Using the straight-line depreciation method, where the asset loses value evenly each year, the accumulated depreciation after three years is $3,000.

NBV Calculation:

$12,000 (original asset value) – $3,000 (accumulated depreciation) = $9,000

Factors That Reduce Net Book Value (NBV)

The net book value of an asset refers to its original cost minus accumulated depreciation, amortization, and impairment losses. Over time, several factors contribute to a decrease in NBV, impacting financial reporting and business valuation.

1. Depreciation

Depreciation is the systematic allocation of an asset’s cost over its useful life. It accounts for the wear and tear an asset undergoes due to regular use. This ensures that businesses recognize the decreasing value of their assets over time instead of reporting their original purchase price.

For example, a company that buys a truck for deliveries cannot report the truck’s full cost on its financial statements indefinitely. Instead, depreciation gradually reduces the truck’s NBV to reflect its actual worth as it ages and wears out.

2. Amortization

Amortization is similar to depreciation but applies to intangible assets such as patents, trademarks, copyrights, and software. Since intangible assets do not have a physical form, their value declines due to legal expiration, competitive market changes, or usage over time.

For instance, a company that purchases a patent for $50,000 with a legal lifespan of 10 years will recognize an annual amortization expense of $5,000 ($50,000 ÷ 10 years). This gradually reduces the NBV of the patent until it reaches zero.

3. Impairment

Impairment occurs when an asset experiences a sudden and significant loss in value. Unlike depreciation and amortization, which are planned reductions, impairment happens due to unforeseen events such as damage, legal restrictions, or market downturns.

For example, if a company owns a factory that is damaged due to a natural disaster, its value may decrease substantially, leading to an impairment charge on the financial statements.

4. Obsolescence

An asset may become obsolete before the end of its useful life due to advancements in technology or changing industry standards. Obsolescence reduces the NBV because the asset is no longer useful, even if it remains functional.

For example, an old computer system may still work, but if new software requires updated hardware, the old system becomes obsolete, forcing the company to replace it sooner than expected.

Determining Eligibility for Depreciation

Depreciation accounts for the loss of value in assets over time. A new car, for example, is worth more and serves better when first purchased than it does after five years of use.

Depreciation ensures that businesses don’t record the original purchase price of an asset indefinitely. Accounting standards and tax regulations define when and how assets can be depreciated.

Not all assets qualify for depreciation. Generally, you can depreciate a tangible asset if:

- You (or your organization) own the asset.

- It’s used to generate revenue.

- It has a remaining useful life of at least one year.

Assets That Can and Cannot Be Depreciated

The following fixed assets are eligible for depreciation:

- Machinery and production equipment

- Company-owned vehicles

- Office buildings owned by the company

- Rental properties generating income

- Intangible assets such as patents, copyrights, and software

The following assets cannot be depreciated:

- Land

- Cash or accounts receivable

- Investments (stocks and bonds)

- Personal property

- Leased assets

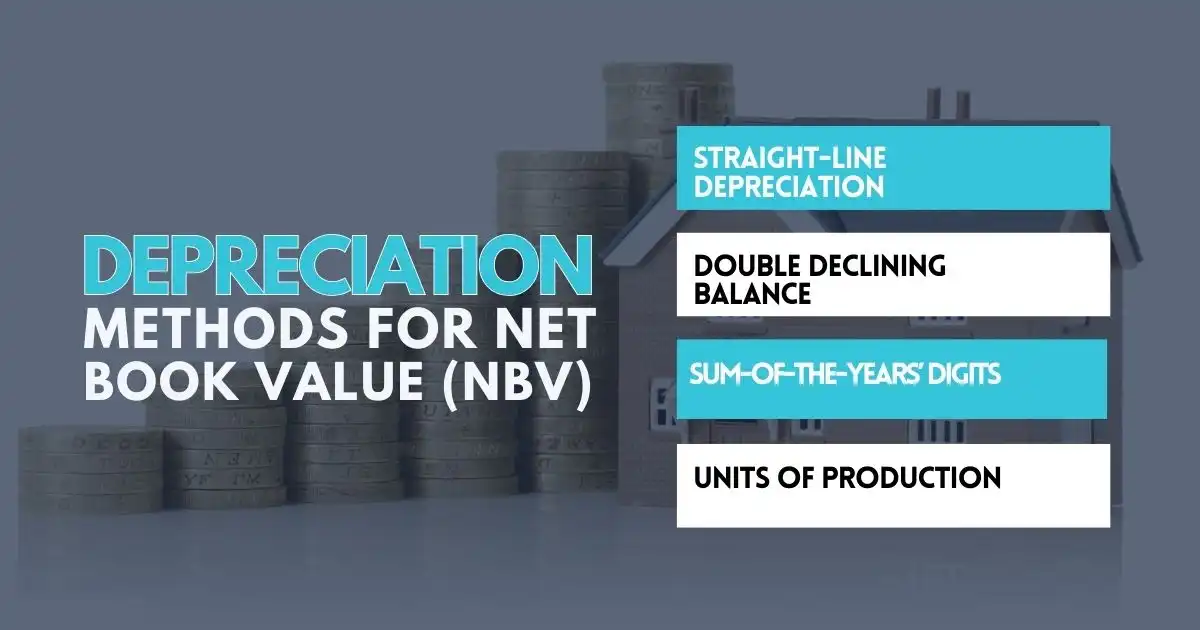

Depreciation Methods for Net Book Value (NBV)

The IRS provides guidance on depreciation methods and timelines. There are four primary methods:

Straight-Line Depreciation

This is the simplest method, where an asset’s value is evenly reduced over its useful life. Depreciation is calculated from the initial value, decreasing at a constant rate until it reaches full depreciation. When graphed, this method forms a straight line.

Straight-line depreciation works well for assets with a predictable loss of value and a known original cost.

Double Declining Balance

This accelerated method applies twice the straight-line depreciation rate to the asset’s remaining value each year. It reflects how many assets lose value more rapidly in their early years.

For example, a $10,000 computer with a four-year lifespan would depreciate as follows:

- Year 1: $5,000 (50% of value)

- Year 2: $2,500 (50% of remaining $5,000)

- Year 3: $1,250

- Year 4: $625

This method is commonly used for technology and electronics that depreciate quickly.

Sum-of-the-Years’ Digits

Another accelerated method, this approach assigns higher depreciation percentages in the early years. It works by summing up the years of an asset’s expected lifespan and allocating depreciation accordingly.

For an asset with a five-year lifespan:

- Year 1: 5/15 = 33%

- Year 2: 4/15 = 27%

- Year 3: 3/15 = 20%

- Year 4: 2/15 = 13%

- Year 5: 1/15 = 7%

Like the double declining balance method, this approach accounts for the asset’s highest value during its early years.

Units of Production

Unlike time-based depreciation, this method calculates depreciation based on actual usage, making it ideal for machinery and equipment.

To apply this method:

- Determine the total number of units the asset will produce over its lifetime.

- Calculate the depreciation rate per unit by dividing the asset’s cost (minus salvage value) by total expected units.

- Multiply the rate by the actual units produced each year to determine depreciation.

For example, a $100,000 bottling machine expected to produce one million bottles with a $10,000 salvage value would depreciate at $0.09 per bottle ($90,000 ÷ 1,000,000). If it produces 200,000 bottles in year one, the depreciation for that year would be $18,000.

This method is useful for high-usage assets, aligning depreciation costs with actual production output.

NBV: More Than Just a Number

Net book value isn’t just an accounting term—it’s a reality check. Many assume an asset’s worth is its purchase price, but depreciation tells a different story. What’s left on the books matters more than what you paid.

Ignoring NBV is like driving with a foggy windshield—you’re moving, but can’t see clearly. If assets lose value faster than expected, it signals inefficiencies, hidden costs, or missed tax benefits.

Smart businesses don’t just track NBV—they use it. From tax planning to investment decisions, NBV keeps your financial strategy sharp. The real question isn’t what an asset was worth—it’s what it’s worth now and how that knowledge shapes your next move.

Are you basing your financial decisions on facts or just guesses?

FAQs

How do you calculate net book value?

Net book value is calculated using the formula: cost less accumulated depreciation equals NBV. This means subtracting total depreciation from the asset’s original cost to determine its book value.

Where is NBV recorded on the balance sheet?

NBV is listed under the property, plant, and equipment balance sheet as part of long-term assets. It represents the remaining value of tangible assets after depreciation.

What is the difference between book value and fair value?

Book value is the asset’s recorded value based on historical cost, while fair value reflects its current market price. Fair value can fluctuate, whereas book value follows accounting calculations.

Why is NBV important in financial reporting?

NBV financial data helps businesses track asset value, manage depreciation, and make informed financial decisions, ensuring compliance with accounting standards.